#3 The Foundation

In many countries the foundation of a house is a matter of pouring a slab of concrete on grade, or putting up some pillars, and calling it a day. Here in Finland, the latter is popular for summer cottages that are not year round in use, since it is a low cost and effective way to build a foundation for buildings that don't have strict requirements for winter. Slab on grade is often used in warmer climates, but even there insulation of the slab is becoming more important to prevent energy losses through the floor.

You can imagine that in a cold climate, I need a foundation that not only is designed to hold up the house, but one that is engineered to prevent heat losses as much as possible, and one that is built in such a way so that any water is drained away from the foundation itself. Having water in contact with the foundation is not only problematic for moisture coming up through the foundation, successive freeze/thaw cycles would also cause damage and can cause the foundation to shift. All this means that getting the foundation done right is a pretty involved process, one that starts by making sure the underground is suitable.

The first thing I did before I even started clearing the area for the house was to get a company involved to do a geological survey of the area. While I was 99% sure there wouldn't be an issue, it's better to be safe than sorry and swallow the bill that comes with it. With the survey, I wanted certainty that there wouldn't be any issues with e.g. clay in the ground, issues with the amount of load the subsurface can handle, and any other things that might lead to issues in the future.

You can prevent a lot of potential issues in advance by doing a small survey yourself. For example, there are maps available which give you an idea of elevation in the area (through e.g. Hillshade maps, see image above) which can be used to find the highest spot on the land. I also took an iron bar and went around the area where the house was planned to go and checked if anything odd was going on. In the end, the survey definitively showed me that there would be no issues what so ever in building on my chosen spot - 1000€ well spent for having this peace of mind.

Next step: clearing the area.

|

| Same location, taken about a year apart - before and after trees cut. |

People might think I had to cut down a lot of trees for this house, but that's not really the case. I should give some background: some of the plot has been used in the past for harvesting (as is common in Finland). I placed the building in an area where the tree density wasn't that high and the paths used for logging in the past are used strategically (for the waste water treatment for example, more in a later blog entry). Now that it doesn't get harvested anymore, it will actually grow more wood over time than there would have been if it had kept being used for harvesting (before I bought it). I actually have been cutting more trees around there since then; certain areas have a bit of a monoculture because of past harvesting. I want to give it a chance to grow back into a more natural forest, while still being able to sustainably use wood for heating as a true renewable source. Part of the off-grid goals.

To put this into another perspective: we had a storm around new year when I started building which took out more trees on my plot (and a lot more by volume considering the size of them) than the ones I cut down - and my plot came out of that storm rather well compared to some of the surrounding areas. Overall, there are so many trees in Finland in general that it's hard to put it into perspective, but even with that major storm in the area causing a lot of fallen trees, the impact is hardly noticeable and will have no issues recovering from it.

|

| Ants... |

I also found several reasonably tall trees that used to have ants nesting in them (no, not termites). This of course kills the tree over time, and can cause it to take other trees down with it, never mind them going down anyway as soon as they catch the wind.

The trees were all cut by hand by yours truly. This means I had the opportunity to properly see the changes that were being introduced, and made sure no trees were cut in excess. I was also able to make sure the resulting wood was stacked properly, and could be used for different things: from firewood to building material for e.g. a wood shed. A trusty Husqvarna (a 550XP) did all the hard work. As you might have noticed by now, the entire project started at the beginning of winter, with the construction of the main building done over winter. This was done on purpose: no leaves or grass or heat to plan/work easier, solid frozen road for heavy equipment to come in, and no bugs! Especially no bugs. Absolutely recommended :)

|

| The Husqvarna and a fire to keep warm. |

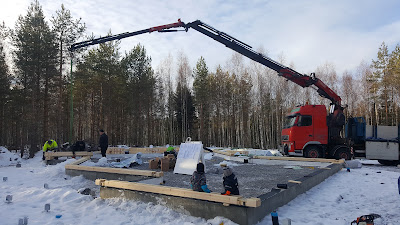

Onto the actual foundation work. I'll start by showing a diagram of how the foundation is constructed.

Unlike a typical slab of concrete, the foundation consists of a poured concrete continuous perimeter in the shape of an upside-down 'T' which will bear the load of the structure and on which the outside walls are placed. Insulation is placed on both sides of this perimeter to prevent frost penetration. In addition, below the insulation there is a layering of different sizes of gravel to increase drainage and work against capillary action. The insulation on the outside is also placed under an angle away from the foundation, again to make sure water drains away from it.

On the inside of the foundation, insulation is placed also vertically against the concrete perimeter. Later when the floor is poured, this will prevent the floor from making contact with the foundation so it won't create a cold bridge. Since this concrete floor will have the underfloor hydronic heating embedded, this also means we're not sending this heat out through the foundation. Because I built this over winter, the floor itself would be poured after the logs and roof are placed since it needs to be warmer to do that.

Of course, all the piping for drainage, power, solar, hot and cold water etc. are put in place while the foundation is constructed. In a cold climate, all water pipes are put below the frost line, and additionally covered with insulation. All the material that is dug out for the foundation (the rocks, dirt and some tree stumps/roots that were removed) stays on site and is used in the surrounding area to stimulate mosses, berry bushes, and other flora (and the fauna it attracts such as bees, dragonflies, etc.).

|

| End result before filling inside and outside with gravel. |

You can see the main foundation and the concrete pillars that will support the deck. Except for two wooden pillars inside the house, only the outside walls of the house are load bearing. Those two pillars that will be on the inside are just to provide additional snow load handling capability.

All the black pipes are drainage pipes and wells for gutters. These are part of the drainage system underneath, with the smaller pipes intended to take the rainwater from the roof gutters. All the rainwater is drained to different corners of the site, and leads to ditches where it will be absorbed into the ground. The incoming water lines are in the back of the house (see in front of the digger in the picture above) and will be located in a technical room there. From here, the inside and outside of the foundation will be filled with gravel, and later on additional insulation; I'll come back to that when I get to discuss the heating systems.

Because we were operating in sub-zero temperatures a heating wire was also embedded in the concrete to help dry the foundation. It only took 24 hours to do this - amazing when you compare that in many other countries building projects stop when it gets a bit chilly outside :)

Comments

Post a Comment